Section 2: Department Stores and Consumption

An important prerequisite of any Empire is its ability to maintain links with its expatriate constituents, its diaspora, and to - in its newly enveloped areas of expansion - establish a near material equivalence with the home land. Importation of material culture from home has historically manifested itself in many ways, from horticulture to cuisine, to cultural practices and festivals. In the British Raj, the availability of English newspapers, the founding of clubs, and events celebrating national commemorations such as Empire Day, or Derby Day, helped to cement (and to exclude) a sense of proximity that alleviated homesickness, reconfirmed allegiances, and in many cases justified the excesses of Empire. In the next part of this exhibition, Shigeru’s preoccupation with the material culture of Japan, its clothes, food, and festive practices is explored. If the films provided visual confirmation of his homeland, the material culture supplied by department stores provided a ‘taste from home’, ameliorating any sense of estrangement, a constant theme in his creative output.

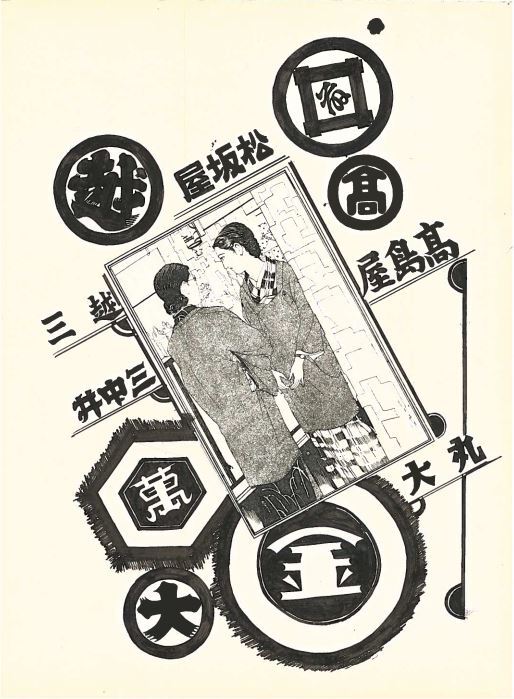

Image 6 features a graphic depicting Japan’s leading department stores of the period. Although department stores had long been associated with modernity and consumer culture both in the West and in Japan, ‘cathedrals of modern commerce’ as Emile Zola famously put it, this image is relatively restrained and conservative. In contrast to the youthful and seductive images of Department stores back in Japan, produced by artists such as Sugiura Hisui (1876-1965) who worked for Mitsukoshi, here the kimono-clad women stare at the shop window demurely, in almost mirrored poses. There is little evidence here of the ‘westernization of retailers and their customers’ lifestyles’, [7] suggested by Fujioka in her study of Japanese Department stores. Nonetheless, the shift in selling modalities from dry goods sold on a haggling basis strongly dominated by men, to the decorum established by fixed prices and guarantees, which resulted in a shift towards female consumption, is well represented. Outside the frame, department store logos jostle with each other for attention. Some of the more well-known department stores depicted here include:

Takashimaya [高島屋]

Daimaru [大丸]

Ichuusan [井中三]

Mitsukoshi [三越]

Matsuzakaya [松坂屋]

Many Japanese department stores had branches throughout the Empire such as Mitsukoshi, or in the case of Minakai, where Shigeru was based, in a specific region. They were highly important cultural conduits and mediators of taste, helping to reinforce the reach of Japanese cultural power; operating much in the same way that fast-food outlets today (may) give a welcome sense of reassurance and familiarity. Jeesoon Hong’s work on the transcultural politics of Japanese department stores, highlights their colonial expansion within East Asia and the lifestyles and social grouping for which they catered [8]. He builds upon the work of a long-line of scholars who have collectively argued that department stores played a, ‘didactic role in introducing and domesticating “Western” customs and culture and “civilizing” the urban middle class’ [9]. If the department store represented the architecture of selling, providing the reassurance of a familiar arena of consumption, then the products themselves seem to have been invested with especial significance by Shigeru.

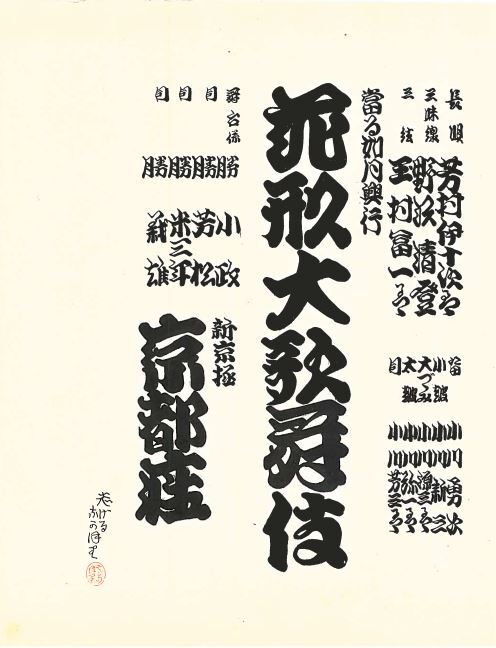

Saké, most especially nihonshu, holds a special place in Japanese culinary culture, forming part of a distinct mythology deeply associated with the countryside. Image 7 depicts various sake brands described in traditional calligraphy or shodō, which neatly combines two important cultural elements. As Michelle T. King suggests through her concept of ‘culinary nationalism’, food and drink culture have always played a strong role in the articulation of national identity.

The labels depicted are:

Seishu Gekkeikan [青酒 月桂冠] Refined sake Gekkeikan

Meishu Chu-Yu- [銘酒 忠勇] Good quality sake Chu-Yu-

- shu Sawa no Tsuru● [酒 澤之鶴]

Hana no Tsuyu [花の露] Flower’s Dew

Fuku-musume [富久娘] Rich, wealthy maiden

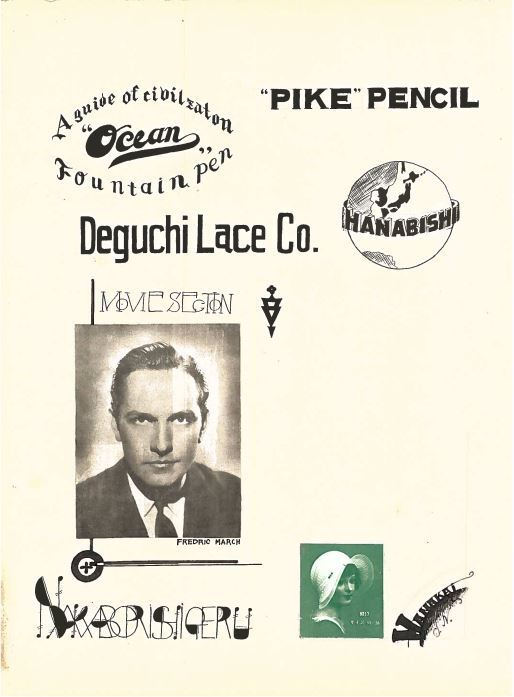

Shigeru was apparently also interested in company logos and typographical design. Image 8 shows several sketches featuring both Japanese and Western companies with a focus on stationery. ‘Pike Pencils’, ‘Ocean’ fountain pens (containing a spelling error ‘Civilzation’ instead of ‘Civilization’), and Deguchi Lace Co. are all depicted. Perhaps most interesting is the logo for the Hanabishi company, its name forming a banner wrapped around the globe with the Japanese Empire prominently shown in black. The unmistakable and unapologetic message is that this is a company with global ambitions, serving and clothing the Japanese Empire proudly.

[7] Rika Fujioka, ‘The Development of Departments Stores in Japan, 1900s-1930s’, Japanese Research in Business History, 31 (2014), p.13.

[8] Jeesoon Hong, ‘Transcultural Politics of Department Stores: Colonialism and Mass Culture in East Asia 1900-1945’, International Journal of Asian Studies, 13(2) 123-50.

[9] Ibid., 125.